Rarámuri

People of the Copper Canyon

Tarahumara or Rarámuri, either way, they are fast…

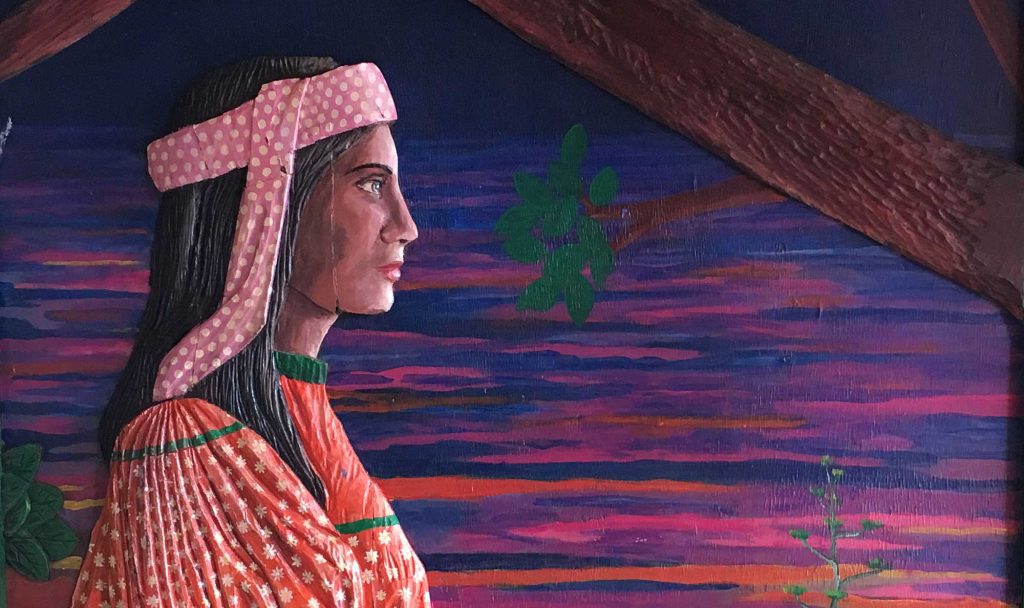

The brightly colored dresses juxtapose the rich earth tones in one of Mexico’s, most rugged regions: the Copper Canyon or “Barrancas del Cobre” as it is known in Spanish. The locals here are proud, resilient and strong…

This is the Rarámuri tribe of indigenous people. They have lived in various regions of the state of Chihuahua since long before the arrival of Spanish conquistadores. They are more commonly known as the Tarahumara, an exonym given to them by the Spaniards and they are easily identified by their distinctive, colorful apparel.

The approximately 70,000 Rarámuri in Chihuahua have been able to preserve their native culture and resist total integration more successfully than any other indigenous group in Mexico. Today they are found living in cities, countryside communities and remote canyons.

Arrival of the Spanish

The Rarámuri lived in small communities with a transhumance and subsistence farming lifestyle when the Spanish conquistadores and Jesuit priests arrived in the early 17th century. With the approach of the Spaniards and subsequent discovery of silver in the region in the 1630s, the Rarámuri retreated into the expansive canyon for refuge.

At four times the size and twice as deep as the Grand Canyon in the United States, the extreme terrain of the massive canyon provided the protection they sought.

Nonetheless, intrepid Jesuit, and to a lesser extent, Franciscan priests established missions and accompanying pueblos in the northern highlands and southern parts of the region. Great efforts were made to Christianize the natives with varying degrees of success. Converted Rarámuri were encouraged to live within the mission/pueblo system. While a small percentage of the converts accepted the invitation, the majority rejected the offer or tried and abandoned it.

When the Jesuits were expelled from Mexico by the Spanish king in 1767, the Rarámuri were left with remnants of Catholic doctrine which they blended with their traditional beliefs.

Religion

The enduring legacy of Catholicism remains a significant factor in Rarámuri life today. Basic doctrine and rituals have been blended with traditional spiritual beliefs to form the religious experience of the majority of the population.

God, the creator of the universe, is manifest as Father Sun, and his wife is Mother Moon, represented as the Virgin Mary by some groups. Semana Santa, Easter Holy Week is one of the most important religious celebrations of the year. This multi-day festival, though, is not focused on the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Instead, it is a combination of Christian and traditional beliefs. The celebration is focused on the struggle between good and evil which they call “Noliruache”. This means spinning or circling in the Rarámuri language. The people are divided into two groups. One group is portrayed as Roman soldiers who represent the forces of good. The opposing group is portrayed as New Testament Pharisees, who represent the devil and evil forces in the world. Included in this group are the “chabochis”, non-Tarahumara people. As part of this representation, the Pharisee group covers themselves with white body paint, either brushed on or painted in dots. At the conclusion of the days of celebration, an effigy of Judas (representing evil) is burned. This event is known as “Quema de Judas” and is done throughout Mexico and Latin America.

Also included during the week are long hours of dancing, accompanied by violins and guitars along with the rattling sounds of ankle shakers called “tenabari”. These shakers are made from dried butterfly cocoons which are filled with sand or small pebbles. The cocoons are tied to leather straps and wrapped around the dancers ankles. The ensuing rattling sound accompanies the stringed instruments being played as the dancers perform the “dutuburi” (a dance of spiritual supplication) for hours at a time. Some Rarámuri runners have reported that the dutuburi is even more exhausting than a marathon as the dancing can last 24 hours or longer with no breaks. Tesqüino, a fermented corn drink central to Rarámuri society, is consumed in copious amounts. Drunkenness is part of the multi-day celebration.

Resistance to Western Influence

The town of Creel on the eastern end of the Copper Canyon region, was named for Enrique Creel, governor of Chihuahua in the early 1900’s. It was originally established in 1907 as a train depot on the Chihuahua-Pacific line as well as an agricultural settlement of a few Mexican families. The goal, determined by the federal government, was to have the Mexican families influence the numerous Rarámuri living in the area to adapt to western culture. This venture was modestly successful at best. A circumferential community of Rarámuri currently live in Creel.

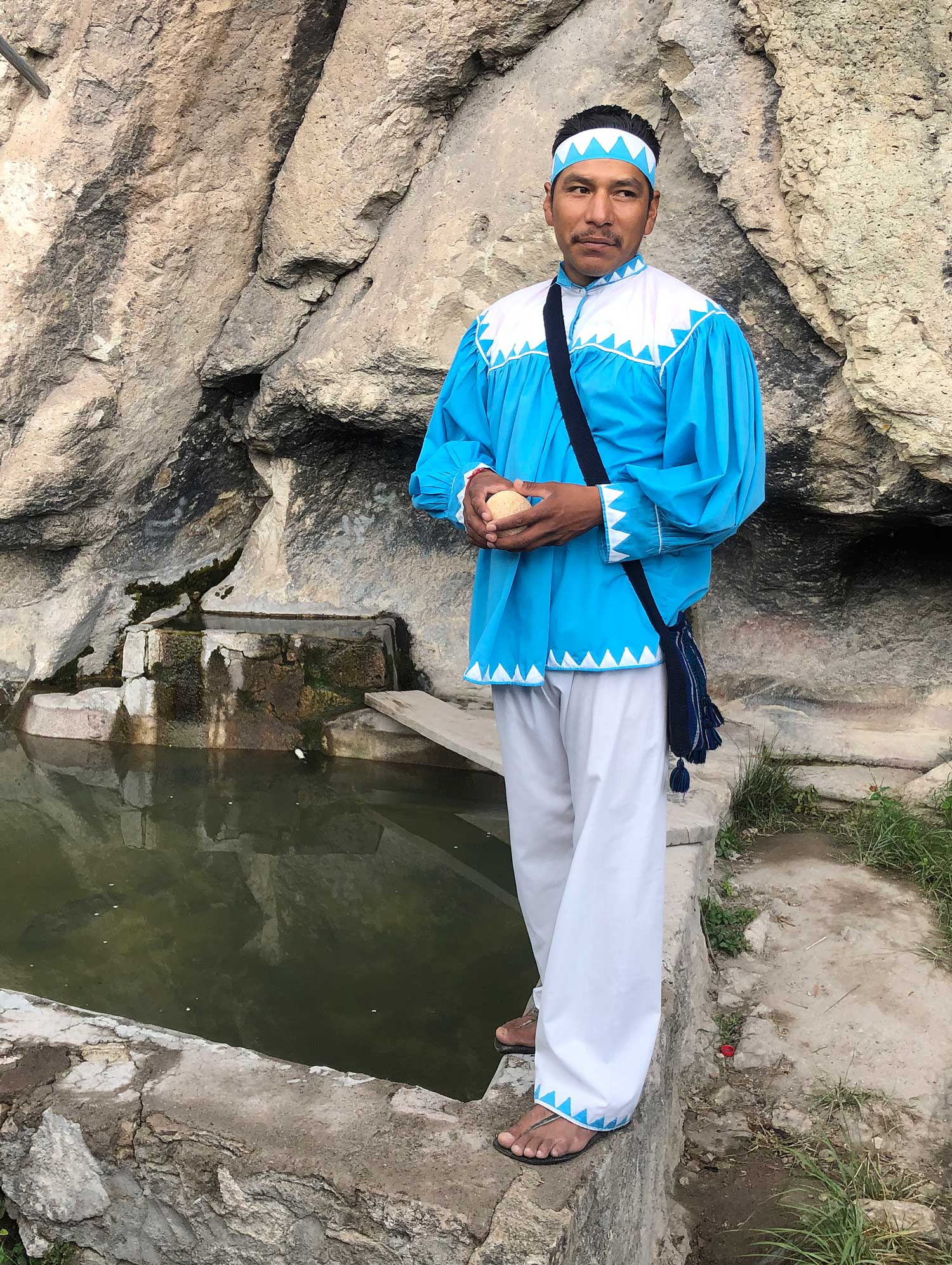

The Rarámuri have chosen to remain separate from western society. The colorful apparel of the women and girls is usually made at home. The full pleated circular skirts and yoked, pleated blouses are embellished with brightly colored fabric triangles. Often, skirts are worn with a waistband called a “pukera”. Sometimes adolescent girls will wear an American-style sweatshirt with the skirts. Men wear an off-white loin cloth called a “zapeta” and a blousy, often brightly colored shirt. A headband called a “koyera” is usually worn, along with huarache sandals. For them, this distinctive apparel is a symbol of opposition to the outside world. Nonetheless, it is not unusual to see the Rarámuri using technology such as smart phones. Unfortunately, some Rarámuri have been exploited by human traffickers and drug cartels in the region.

Education

The Mexican government has mandated that Rarámuri children must attend school. Communities generally consist of several modest rural homes surrounded by fields for farming, a church and a school. For the most part, these were established by Jesuit or Franciscan priests in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the children assigned to attend these schools live far enough away that they live onsite as boarding students.

These families may walk for three days to bring their children to live at the school. The distance and rugged terrain prevent the children from going home on the weekends and some of them may live at the school for ten months at a time, sometimes longer.

According to some studies, large numbers of children do not attend school and illiteracy is disproportionate to the general population. Most of the Rarámuri population speaks both Spanish and the Rarámuri language.

Homes

The Rarámuri generally live in small areas called “ranchos”, rural patches of land with a water source and arable terrain for subsistence farming. One room adobe, stone or wooden houses are connected to electricity where it is available. They are frequently without running water, but have a large cistern next to the house from which they draw water as needed.

For families living further in the canyon, the two basic needs are the same, a water source and a patch to grow corn and beans. Looking down into the canyon, homes are easily identified by their metal roofs. Some families live in small homes hugging a cliff wall or even in caves. Caves have provided families comfortable homes for decades. Cave homes often have all the furnishings of traditional homes, including wood burning stoves, beds, chairs and cabinets.

The Rarámuri are Runners

The Rarámuri are probably best known for their exceptional athletic ability as long distance runners. The remote nature of their communities make foot travel the most logical form of transportation and communication relay. Studies have determined that their diet, very low in protein and fat, and high in carbohydrates like pinto beans and corn, contribute to their high levels of endurance. Running is essential to the daily life both men and women. While long distance runners around the world wear expensive footwear, the Rarámuri wear huaraches, simple sandals handmade from tire tread and leather strings.

Daily Life and Customs

The Rarámuri are probably best known for their exceptional athletic ability as long distance runners. The remote nature of their communities make foot travel the most logical form of transportation and communication relay. Studies have determined that their diet, which is very low in protein and fat, and high in carbohydrates such as pinto beans and corn, contributes to their high levels of endurance. Running is essential to the daily life of both men and women. While long distance runners around the world wear expensive footwear, the Rarámuri wear huaraches, simple sandals handmade from tire tread and leather strings.

Running is so much a part of daily life that it is even used in search of food. When occasionally hunting deer or wild turkeys, men will chase the animal until it drops from exhaustion. This may happen over the course of a couple of days.

Athletic competitions also involve extreme amounts of running. Men play a ball game called “rarajipari”. Using a hand carved wooden baseball-sized ball called a “komakali”, men form two teams and kick the ball through the mountain ravines. The finish line may be between fifty and one hundred miles away. Locals can be found along the game path cheering on the players and providing water and refreshments. It is not uncommon for competitors to make wagers on the game, including their own clothing, piece by piece. Some players will wear multiple layers of clothing to have plenty to wager. The game continues for hours, sometimes for two days, until one of the teams crosses the finish line. The winning team divides up the wagered clothing as their prize.

Women have their own game called “dowerami”. Dowerami involves running through the rugged countryside while guiding wooden rings with two-pronged sticks.

Unemployment is an issue for the Rarámuri. Being modestly educated and preferring to not associate themselves with “chabochis”, their employable skills are limited. Some earn a living as tour guides. Since they are a culturally shy and reserved people, this is not a field in which many would feel comfortable. Men are rarely seen in the community as they are involved in subsistence farming or collecting firewood and other materials.

Women are more visible in society as they sell handicrafts they make in their homes. Sewing is a large part of the life of Rarámuri women as well as their livelihood. They make tortilla warmers, aprons, dresses and other household items to be sold as well as jewelry and fabric dolls. Many of the goods are sewn by hand with needle and thread; a few are sewn with machines. Children are also commonly seen selling these handmade goods in tourist areas. It is not usual to see young mothers selling handmade crafts with a young child at her side and a baby strapped on her back with a “rebozo”, a Mexican shawl.

In Conclusion

The Rarámuri people have been a source of curiosity and research for decades. By maintaining their traditional lifestyle and separating themselves from society at large, they give us the opportunity to look into the past in a way. As the world around them changes at a unprecedented rate, their simple, nature based lifestyle has changed very little. Family, community, tesqüino and running — those are the basics of life that have kept this elusive people going for hundreds of years, if not more.